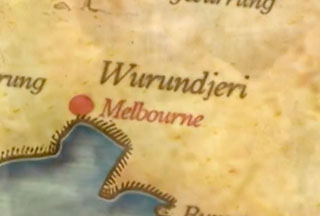

Coranderrk Aboriginal Station is located on Wurundjeri country, specifically on the Yarra Flats and is bordered by the Yarra River, Badger Creek, Watts River and the slopes of Mount Riddle.

To learn more about Aboriginal stations check out our history timeline entry Creation of reserve system.

It was established for the people of the Kulin Nation, an alliance formed by five language groups - Woi Wurrung/Wurundjeri, Boon Wurrung, Wadawurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung and Taungurung - but was home to many other mobs as well.

Watch

- First Australians: Season 1 Episode 3, Freedom For Our Lifetime (SBS OnDemand)

The threat of extinction hovers over the first Australians of Victoria at the time Wurundjeri clan leader Simon Wonga seeks land from the authorities.

Opening

Acheron & Mohican Station

In 1859 Uncle Simon Wonga (Wurundjeri Ngurungaeta) contacted Assistant Protector William Thomas, requesting land for farming on behalf of the Taungurung people. Thomas was able to organise a meeting with the Board of Land and Works to discuss this request, at this meeting Thomas was joined by a group of Taungurung men and Uncle Wonga who acted as an interpreter. The meeting was a success and Acheron Station was established in 1859.

Over the next year, the Acheron residents cleared the land, fenced about 17 acres and planted seven acres of crops. After all the work, they had put into the land the government ordered them to move south to Mohican station. Despite their protests, they were forced to move and the government took over Acheron, pulling down the fences and allowing the cattle to destroy the crops. The land at Mohican station was not suitable for farming and was extremely cold - even the colonists would not settle there.

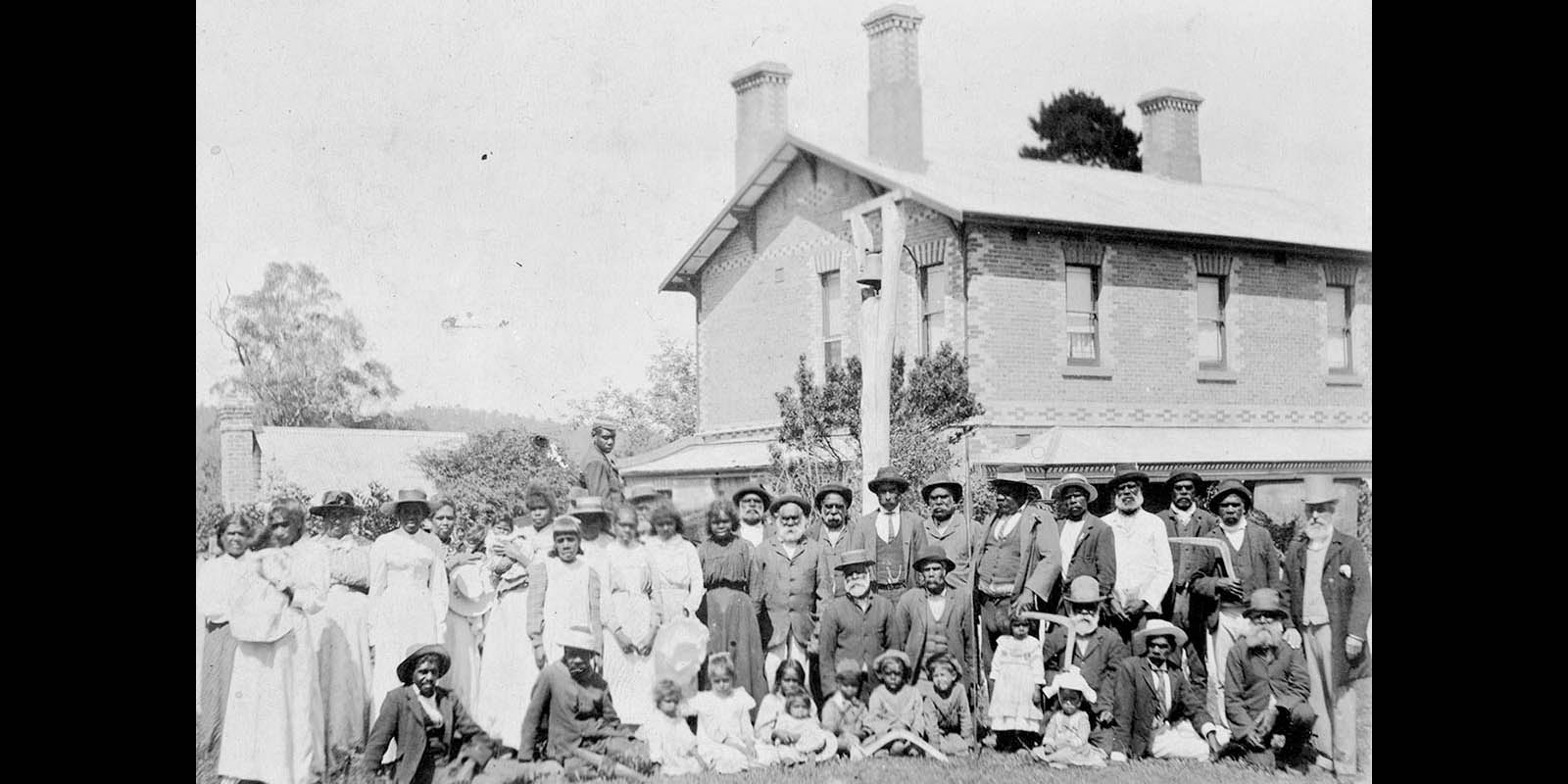

William Barak and the Aboriginal community of Coranderrk. Image source: National Museum Australia, Coranderrk.

Establishment of Coranderrk

Wurundjeri people had been experiencing similar setbacks after many settlers moved into their encampment at Yering and they were made to leave. John Green, a Scottish Presbyterian lay preacher, and his wife, Mary Green, had become friends with the Wurundjeri people and were trying to help them secure new land. After a failed attempt to re-establish Acheron station the Wurundjeri and Taungurung families, accompanied by the Greens walked across the Yarra Ranges eventually settling in an area where the Yarra River and Badger Creek met. This site was named Coranderrk - the Woi Wurrung name for the native Christmas Bush that grew in the area.

Uncle Wonga formed a group of 15 Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Boon Wurrung men to travel to Melbourne to request ownership of the site they had settled on. The group brought gifts with them, handmade rugs and blankets for the Queen and traditional weapons for Prince Albert, which they gave to Governor Henry Barkley. Uncle Wonga delivered a strong speech in Woi Wurrung language and had William Thomas translate for him.

Their meeting was a success and the following month it was announced in Victoria’s Government Gazette that the Governor had ‘temporarily reserved’ 2300 acres (extended to 4850 acres a few years later) to use as a reserve in June 1863. Later that year the people at Coranderrk were sent a copy of a letter passing on the Queen’s thanks for Uncle Wonga’s address and her promise of protection.

Life on Coranderrk

Coranderrk was officially made a reserve in 1863, it quickly became Victoria’s biggest reserve as well as a thriving farming community.

John Green was appointed as the manager of the reserve, this was beneficial to the residents as not only was he a friend to many of them he also believed that the Kulin people should be allowed to determine their own needs and manage their own affairs. This approach meant residents were able to maintain many of their cultural practises and traditions while living in a government reserve. The residents formed a court assembly that Green sat in and together, they decided on the rules of conduct for the station and the punishments for breaking those rules.

The residents of Coranderrk credited its success with their own hard work and the white men and women who lived at Coranderrk including Green were seen more as helpers rather than masters.

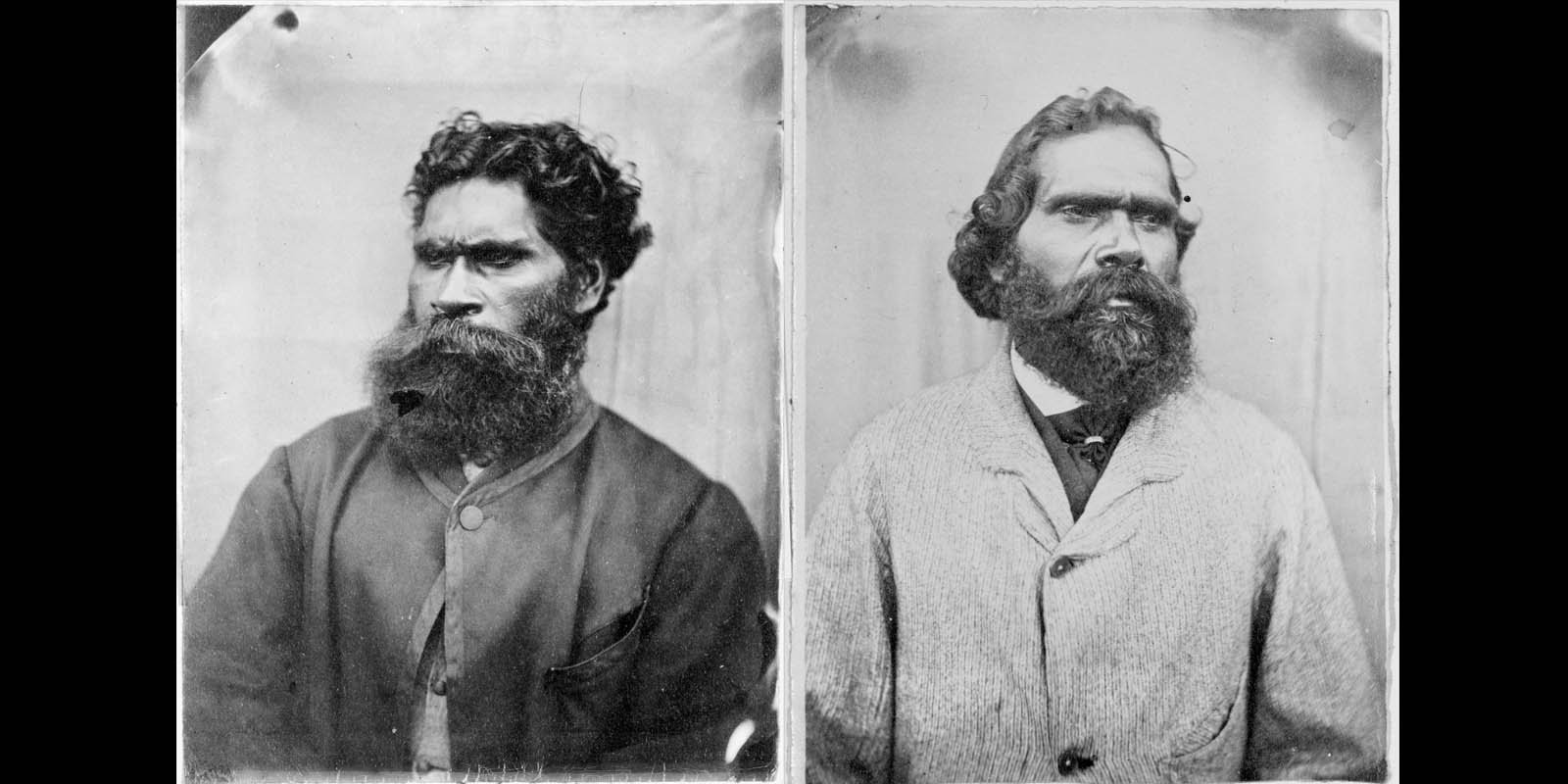

Uncle William Barak & Uncle Simon Wonga. Image sources: State Library Victoria; William Barak - age 33 & Simon Wonga - age 37.

Attempted shut down

In 1874 Uncle William Barak became the new Wurundjeri Ngurungaeta after Uncle Wonga passed away. Uncle Barak’s leadership was very quickly put to the test when Coranderrk came under threat of closure.

The Aboriginal Protection Board organised John Greens removal from Coranderrk as manager. There had been issues arising between members of the board and Green over the way he was managing Coranderrk. Board Secretary Smyth gradually removed the stations management from the residents and hired white labour to manage the Hops fields. The residents were forced to work under these white labourers for no pay - a big change from the independent life they had been living until then. The Protection Board was also under pressure to subdivide the land and shift residents away from their homes to a remote spot on the Murray River. This was strongly opposed by the residents of Coranderrk

Uncle Barak’s nephews, Uncle Robert Wandin and Uncle Thomas Dunolly, were skilled writers and assisted him in forming a series of letters and petitions to the Government. In an interview that year, Uncle Barak famously said

“Me no leave it, Yarra, my country. There's no mountains for me on the Murray.”

Uncle Barak also led a large group of people on a walk to Parliament House - recreating a walk he had previously done with his cousin, Uncle Wonga, when they had sought permission to establish Coranderrk.

Uncle Barak met with Graham Berry, the then chief secretary of Victoria, who he was able to convince to stop the closure of Coranderrk. Unfortunately, the quality of life at Coranderrk deteriorated due to the Board’s mismanagement and severe cuts to funding.

1881 Inquiry

In 1881 Uncle Barak organised a third walk to Melbourne after Coranderrk was once again being threatened. He led 22 men along the 60km journey from Coranderrk to Parliament House. They met with Chief-Secretary Graham Berry, who personally agreed with their requests, but did not believe Parliament would. As a result, Berry appointed a Board of Inquiry to investigate the conditions and management of Coranderrk. You can read more about the 1881 Inquiry on our history timeline.

Aboriginal girls, Coranderrk, Vic. Image source: State Library Victoria.

Closure

In passing the Aborigines Protection Act 1886, the Colonial Government inflicted huge harm to the Aboriginal Community by separating those who were ‘half-caste’ and those who were ‘full-blood.’ Those who were considered ‘full-blood’ were allowed to continue living on reserves and missions while ‘half-castes’ would be removed and forced into society to 'assimilate'. You can read ore about the protection legislation in our history timeline entry "Protection" legislation introduced in Victoria.

Despite all the work put in by Uncle Barak, Uncle Wonga and the residents of Coranderrk, this Act meant most of the young people of Coranderrk were forced to leave the station. This led to the upkeep and running of the station being left to an ageing population. Uncle Barak sadly passed away in 1903, causing another huge blow to the Coranderrk community.

Due to the decline in numbers the government once again began arguing for its closure and in 1924 Coranderrk was officially shut down. Residents were encouraged to move to the Lake Tyers Mission, however some refused to leave their homes and instead lived the remainder of their lives on Coranderrk.

Coranderrk Today

In 1998 Coranderrk cemetery was handed back to the Wurundjeri people and over the following decade Wurundjeri was able to acquire a further 119 hectares. Coranderrk was also added to the Australian National Heritage List on 7 June 2011.

Coranderrk remains to this day a place of huge significance for Wurundjeri and other Kulin people.

Listen

Sources

- Minutes of Evidence, Excerpt - history of Coranderrk

- Wurundjeri Tribe Council

- National Museum Australia, Coranderrk

- Minutes of Evidence, The Coranderrk Inquiry

- State Library of Victoria, Coranderrk mission

- Department of Agriculture, water and the Environment, National Heritage Places - Coranderrk

- Only Melbourne, Coranderrk Aboriginal Station