This article is about the Mabo legal case, which recognised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights to land in Australian law, and the story of the man behind these important events, Uncle Eddie Koiki Mabo, who will be referred to as Uncle Koiki.

Uncle Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo

Uncle Edward ‘Koiki’ Mabo was born in 1936, in Las on the island of Mer (Murray Island) in the Torres Strait to ‘Robert’ Zesou Sambo and ‘Annie’ Poipe, née Mabo. His mother passed away shortly after his birth and he was adopted by his maternal Uncle and Aunt, Benny and Maiga Mabo in line with Islander custom.

His first language was Meriam and his childhood was immersed in his Island culture. As a young man he worked as a teacher’s aide and as an interpreter for a medical research team before he left for the mainland. In Queensland he worked aboard fishing boats, as a cane cutter and railway worker. During this time he met and later married Aunty Ernestine Bonita ‘Netta’ Nehow, a South Sea Islander woman.

Aunty Bonita with Uncle Koiki. ABC.

Career in politics and education

Uncle Koiki was involved in politics and community organising well before his famous court case. In the 1960s he first became involved in the trade union movement as a union representative for Torres Strait Islander people in a range of different projects and labour boards.

During this time, Uncle Koiki became a prominent leader for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Queensland. He was the secretary of the Aborigines Advancement League (Queensland) from 1962 to 1969 and in 1970 he became president of the Council for the Rights of Indigenous People. He was also involved in the campaign for the 1967 referendum to have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people be included in the census and allow the national Australian Government to make laws that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, rather than the states.

In the 60s and 70s, Uncle Koiki made connections with local universities. He was employed as a gardener at James Cook University and used his lunch breaks to study Torres Strait Islander history in the University library. His interest in the education sector and strong desire to ensure his children could maintain their language and culture led him to set up the Black Community School in Townsville in 1973 along with Burnum Burnum (then known as Harry Penrith). In the 70s he was also involved in the National Aboriginal Education Committee and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Education Advisory Committee. He also worked as a vocational officer at the Commonwealth Employment Service as from 1978-81.

In addition to working in political and educational organisations, Uncle Koiki was strongly involved in the arts, maintaining the cultural practices he learned as a child. He was a performer of Islander music and dance and was a member of the Australia Council for the Arts for four years from 1974.

"It will be there for me when I go back" - Uncle Koiki’s legal fight for land

Lead up to the Mabo case

In 1981, Uncle Koiki gave a speech at James Cook University about ownership and inheritance of land for Meriam people on Mer. He explained to the crowd that the land on Mer belonged to the Torres Strait Islander people as their ancestors had lived there for thousands of years.

After his speech, the historian Professor Henry Reynolds asked Uncle Koiki if he was sure the land he grew up on belonged to his family. Uncle Koiki replied:

Oh yes, everybody knows it's Mabo land and my sister is looking after it. And as long as I want that land, it will be there for me when I go back.

Professor Reynolds then told him that he and other Meriam people were not the legal owners of land they had inherited in line with their custom and tradition. Rather, in Australian law it was categorised as belonging to the Crown. Shocked by this information and encouraged by people he had met in his work in the union, political, community and education sectors, he and a group of other Meriam people decided to take a case to the High Court of Australia to establish ownership of their land in the legal system.

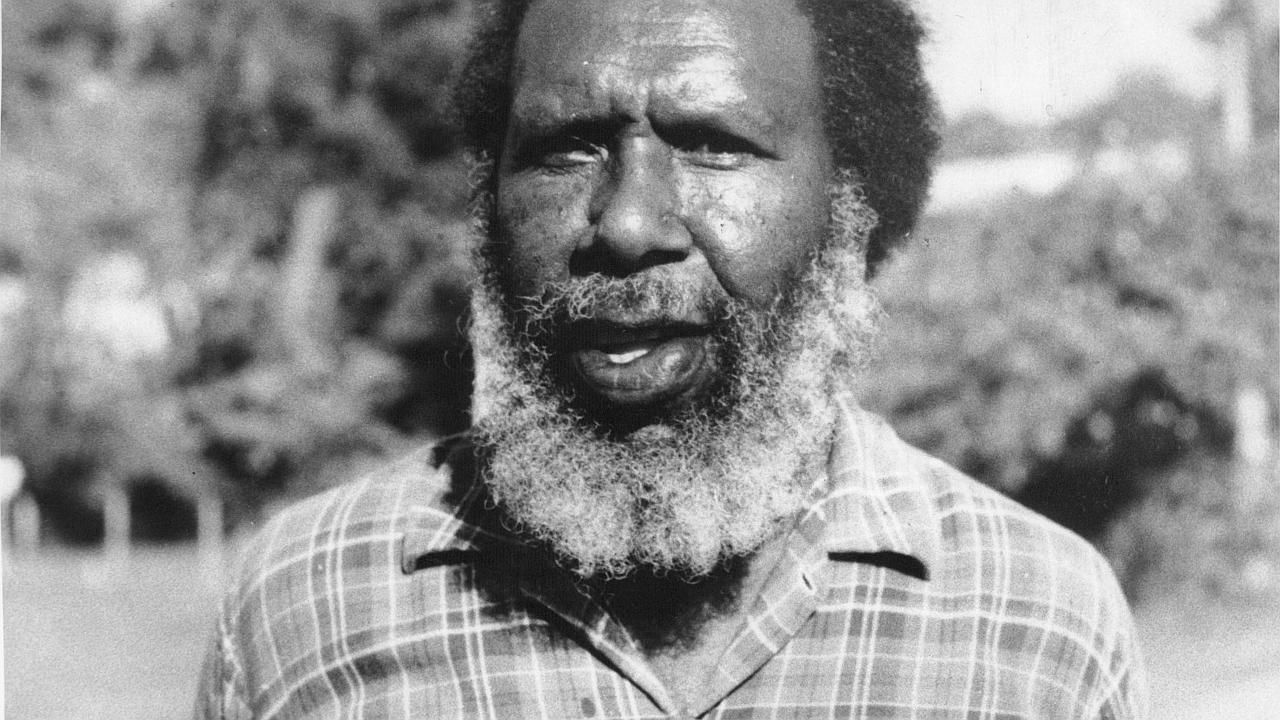

Image: Uncle Eddie Koiki Mabo in Townsville, 1991. Photograph by Bethyl Mabo, AIATSIS.

Mabo v. Queensland Number 1

On 20 May 1982 Uncle Koiki, along with Islanders, Uncle Sam and Rev. David Passi, Aunty Celuia Mapo Salee, and Uncle James Rice lodged a claim for their land and began legal proceedings. Because Uncle Koiki was the key person named in the case, it is commonly known as the ‘Mabo case.’

Uncle Koiki explained why he and the others had launched the case by stating:

My name is Edward Mabo, but my island name is Koiki. My family has occupied the land here for hundreds of years before Captain Cook was born. They are now trying to say I cannot own it. The present Queensland Government is a friendly enemy of the black people as they like to give you the bible and take away your land. We should stop calling them boss. We must be proud to live in our own palm leaf houses like our fathers before us.

While the case was going through the courts, the Queensland Government passed the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act in a deliberate attempt to stop Uncle Koiki and other claimants from gaining their land. The Act stated the Islands were transferred to (and therefore owned by) the state of Queensland in 1879. However in 1988, the High Court ruled that this Act was invalid.

In 1990, the Supreme Court handed down its findings in the Mabo case. The Judge, Justice Martin Moynihan determined that Uncle Koiki had not officially been adopted by Benny and Maiga Mabo in line with Australian law and therefore could not inherit their ancestral lands. However, this decision ignored the importance of cultural lore in the Islands.

He argued that while the Community could prove they have ‘native title’ (meaning they had observed traditional laws and customs and had continuously occupied and inherited the land on Mer since before colonisation) because Uncle Koiki was not adopted by Benny Mabo under Australian law, he had no claim to Mabo land.

Mabo v. Queensland Number 2

Despite his disappointment at the first ruling, Uncle Koiki decided to continue the fight along with Rev. David Passi and Uncle James Rice (Aunty Celuia Mapo Salee had passed away and Uncle Sam Passi had withdrawn his claim). This time however, they focused on proving they had communal rights to land as Meriam people, rather than as individuals. Hearings began in the High Court in May 1991 and a verdict was delivered on 3 June 1992.

A majority of judges found that Meriam people have ‘native title’ to their land, based on their traditional connection to and occupation of their Country that can be recognised in Australian law. The Court found that they had these rights to land despite the claims by the British that Australia was ‘terra nullius’ (land belonging to no-one) when they arrived in 1788. Uncle Koiki’s role in this landmark judgment was summed up by Bryan Keon-Cohen, junior counsel in both cases who stated:

...without Eddie Mabo there was no case.

The ruling in the Mabo case was the first time in Australian history that colonisers and their law recognised that Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people have rights to land based on their culture and lore. It also overturned the idea of terra nullius. This decision was and still is seen as a momentous victory by the Indigenous rights movement.

Sadly, Uncle Koiki had developed lung cancer in 1990 and passed away on the 21st January 1991. He was survived by his wife, two sons, five daughters, and three adopted children. The Federal government assisted Mabo’s relatives to transfer his remains to the Murray Islands and on 18th September 1995 Uncle Koiki was reburied at Las. Uncle Koiki is rightly still remembered as a strong fighter for the rights of his people and a significant figure in Australian history.

For more information about Uncle Koiki and the Mabo case, you can visit the resources below:

Image: Rev. Dave Passi, Uncle Eddie Mabo, barrister Bryan Keon-Cohen and Uncle James Rice outside the Queensland Supreme Court, 1989. Nationla Museum Australia.

ABC News segment commemorating the twenty year anniversary of the decision brought down by the High Court of Australia.

Film/TV

- A film about the life of Uncle Koiki and his quest for justice in the Court system.

Mabo: Life of an Island Man (1997, Trevor Graham)

- Mabo: Life of an Island Man is a 1997 documentary on the life of Uncle Koiki. It was awarded Best Documentary at the Australian Film Institute Awards and the Sydney Film Festival.

First Australians Season 1 Episode 7 - We Are No Longer Shadows (Rachel Perkins)

- We Are No Longer Shadows - episode of the famous documentary series focusing on Uncle Koiki and his legal case.

Books

Eddie Koiki Mabo: His Life and Struggle for Land Rights (Eddie Mabo and Noel Loos)

- Uncle Koiki’s story told largely in his own words. It covers his years as a boy on the island of Mer through to his struggle within the union cause and the black rights movement, as well as his legal case.

Sources used in writing this article:

- Eddie Koiki Mabo, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Case summary: Mabo v Queensland, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Mabo case, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Mabo, Edward Koiki (Eddie) (1936–1992), Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Let’s talk – 20th anniversary of Mabo, Reconciliation Australia

- Mabo – a timeline, Australian Broadcasting Corporation.